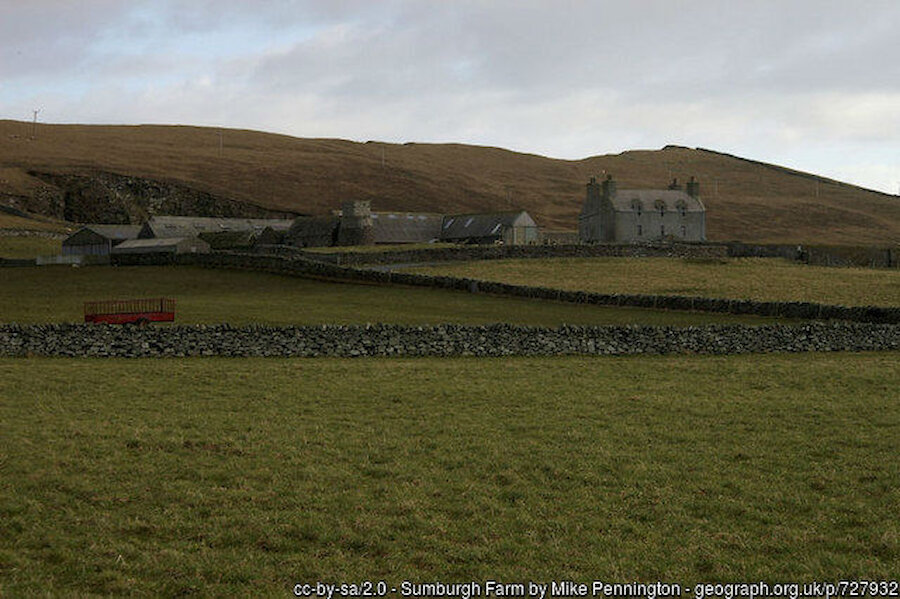

Shetland’s south mainland is a fascinating part of the islands, and nowhere is that fascination more concentrated than in a couple of square miles at Sumburgh, the southern limit of the mainland. Here, a day’s walk encompasses almost five millennia.

It's easiest, though, to consider the area’s story chronologically. The evidence of human activity goes back to the Neolithic, but here, too, is Shetland’s main airport. The threads connecting ancient to modern are unbroken and, sometimes, interwoven.