The flour shortage provoked by the Covid-19 pandemic was brief as far as Shetland was concerned, but the lack of such a basic ingredient led me – and maybe others – to reflect on the self-sufficiency that was the ancient normal.

Those thoughts crystallised when, out walking not far from home recently, I explored the remains of some very old watermills. They remind us that, for most of the time that Shetland has been inhabited, flour didn’t come from a local shop or supermarket – and ultimately from much farther away. Only a couple of centuries ago, crofters had to grind grain either by hand in a quern (essentially, a very large pestle and mortar) or by taking it to one of the many mills scattered throughout the islands.

A vertical shaft connected the paddles to the millstones in the room above. One of these was fixed and the other driven by the power of the water. There was no gearing and the stone turned at the same speed as the paddles.

As the photograph shows, grain was (in most cases) fed into a hole in the centre of the millstone via a wooden hopper. As the stone turned, the grain was ground, to emerge around the circumference of the stones and gather in a surrounding stone or wooden tray. It wasn’t a particularly efficient machine in its use of water, but if there was a good supply from a loch or stream, that didn’t greatly matter, as long as the mill did its job.

Mill ponds were created by constructing a small dam to raise the water level of an existing loch or pond as far as practicable. Indeed, at the Loch of Gershon (pictured above), there is evidence of a beach at the former, higher water level. The dam incorporated a sluice-gate that could be opened when a strong flow of water was needed for milling. Downstream, further sluices were used to divert the water through the mill when required.

As Dr Ian Tait, Curator of the Shetland Museum, points out in his encyclopaedic study, Shetland Vernacular Buildings 1600-1900 (Shetland Times, Lerwick, 2012), these mills had “been perfected for subsistence economies, simple to construct from limited resources, eliminating the need for gearing, and using a minimum of iron.”

Several mills would usually be built on the same section of stream, re-using the water. It’s common to find groups of between three and six, and in a few locations there were more. The mills might be owned by individual crofters, or shared between several families.

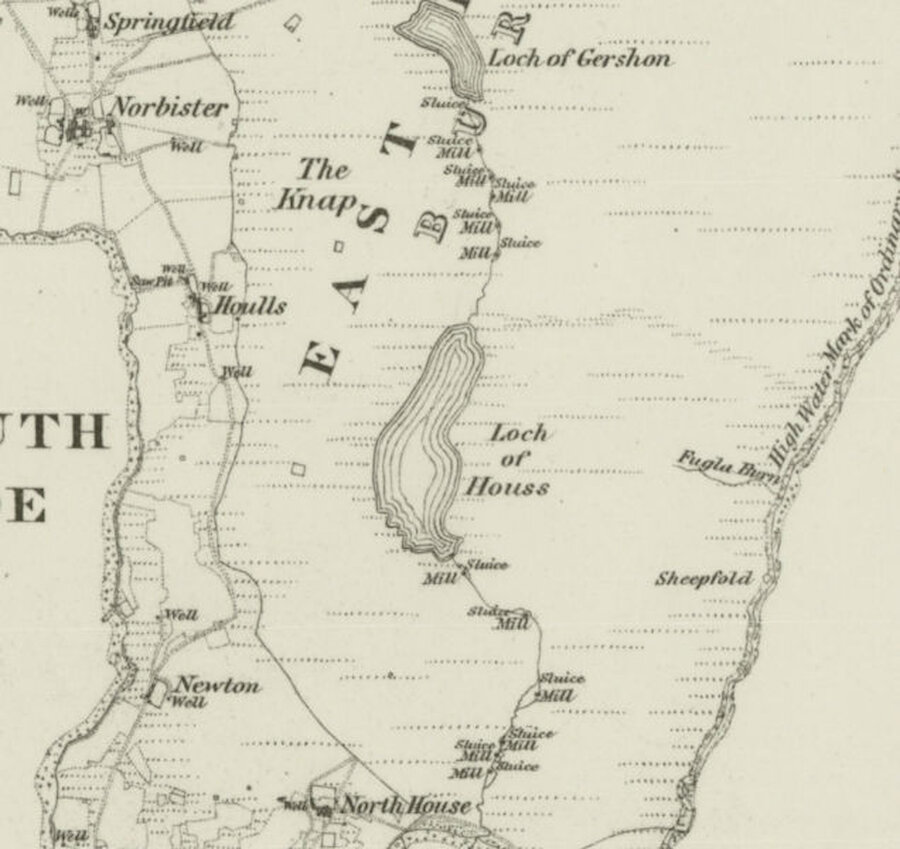

What’s striking is how many there could be in a relatively small area. For example, looking at the first edition of the Ordnance Survey map for part of East Burra Isle, we find no fewer than 11 mills fed by two lochs, five on the section between the higher and lower lochs and six between the lower loch and the sea.

Within half a mile, there were more mills on a different stream and, not much farther away on West Burra, the others pictured at the head of this article.

It seems that this form of mill was first used in Greece and what is now Turkey as early as the 3rd century BC, but they were also to be found elsewhere around the Mediterranean. Examples of the same technology are to be found across Scandinavia and are known from Norway, leading to their being labelled ‘Norse’ mills, despite that much wider distribution.

It’s thought that the design reached Scandinavia via Ireland, where such mills existed before the Vikings arrived. The assumption is that the Vikings brought the design to Shetland, Orkney, and the Western Isles, so there may have been mills of this kind in Shetland for 1,100 years or so.

Dr Tait mentions several Shetland place-names that indicate the presence of mills during the Norse period. That said, no mill in Shetland has been positively dated to earlier than the 17th century, but perhaps a Viking period one may yet be identified.

Can we exclude the possibility that the pre-Viking inhabitants of Shetland built mills, perhaps on the same sites? Perhaps we shouldn’t. A watermill dated to the Pictish period has been discovered at an early Christian monastery in Portmahomack, Easter Ross. Did Irish monks, rather than Vikings, bring knowledge of mills to Shetland, as they appear to have done at Portmahomack? Or were such mills already known among Pictish peoples? We may never know.

If the mill sites we see today have been in use for longer than we’ve so far been able to confirm, it could be because those sites were often on relatively soft ground by streams. The mills would thus be prone to settlement and may have had to be rebuilt at intervals over the centuries.

The 19th century saw the construction of three much larger mills. These were at Quendale in the south mainland; in the central valley of Weisdale; and at Girlsta, just a few miles away but on the east coast.

Quendale Mill dates from 1867 and was in use until 1948. It lay unused for four decades before being restored to working order by the South Mainland Community History Group, with support from the Shetland Amenity Trust. Oats and bere were ground here and farmers and crofters from a very wide area used the mill. It’s normally possible to visit the mill between mid April and mid October, though opening in 2020 has been delayed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

For anyone used to large watermills, Quendale Mill feels very familiar. It’s what’s known as an overshot watermill, meaning that the water arrives via a trough and pours over the top of the mill, causing the wheel to turn. The trough is fed from a millpond a little way to the west. Inside, the machinery is on a very impressive scale.

Weisdale Mill was built in 1855 and was, in its day, the islands’ largest mill. It operated until the 1930s, when it was converted to form a slaughterhouse and butcher’s shop. During the Second World War, it supplied the large numbers of troops stationed in Shetland and, on one occasion, the building came under fire from an enemy aircraft, fortunately without injury.

The slaughterhouse and shop closed in 1982 and the building was taken over by Shetland Arts. Conversion into an art gallery, with a shop and conservatory café, followed in 1994 and since then the Bonhoga Gallery, as it’s known,has been a very active venue, presenting several exhibitions each year and offering a very appealing option for those in search of tea, coffee and cake, or a light lunch.

The mill at Girlsta was built by one of Shetland’s best-known firms, Hay & Company, in 1861, to serve the surrounding agricultural community. There was a mill, a kiln and a store, and this was another overshot watermill, the water in this case coming from the Loch of Girlsta a few hundred metres to the north.

Girlsta Mill hasn’t been restored, and the part of the building that housed the milling equipment is derelict. However, the remainder serves as a store for the adjacent salmon hatchery.

Water provided the power for all of these mills, but there was also at least one windmill in Shetland. It was constructed in the mid-19th century at the highest point on the island of South Havera. There is no stream on the island to provide water power, so the inhabitants – of whom there were around 50 at one point – did their best to harness the breeze. Today, just the shell remains and the last inhabitants left in 1923, though sheep are still grazed there.

Of course, Shetland’s ancient self-sufficiency didn’t extend only to flour. Much of the fertile land that today is devoted to grazing sheep or cattle was once cultivated, and as well as grain crops it produced potatoes, turnips and other vegetables. Cabbages and other crops were grown in plantiecrubs, small stone enclosures that excluded rabbits and sheep. Crofters would keep at least one cow for milk, as well as sheep; but the sea was an obvious source of food, and Shetland’s fishing heritage is as old as human settlement, going back more than 5,000 years.

Fishing and livestock are still very much part of the Shetland scene but, these days, there’s increasing interest in growing a diverse range of food in the islands. There are dozens of Polycrubs – the stormproof greenhouse conceived, designed and built in Shetland, but now successfully exported to many other communities. In these, it’s possible to raise a huge variety of vegetables, salads and fruit.

Commercial growing of vegetables, salads and soft fruit has taken off, too, for example in the west mainland at Transition Turriefield and in Yell and Unst.

It’s often said that life will be different after Covid-19. If people choose to work from home and spend less time commuting, chances are that they’ll have more time to devote to gardening and baking. It’s a lot harder to imagine the return of those old horizontal mills, but they do remind us of that earlier, more self-sufficient lifestyle – and encourage us to switch on the oven!