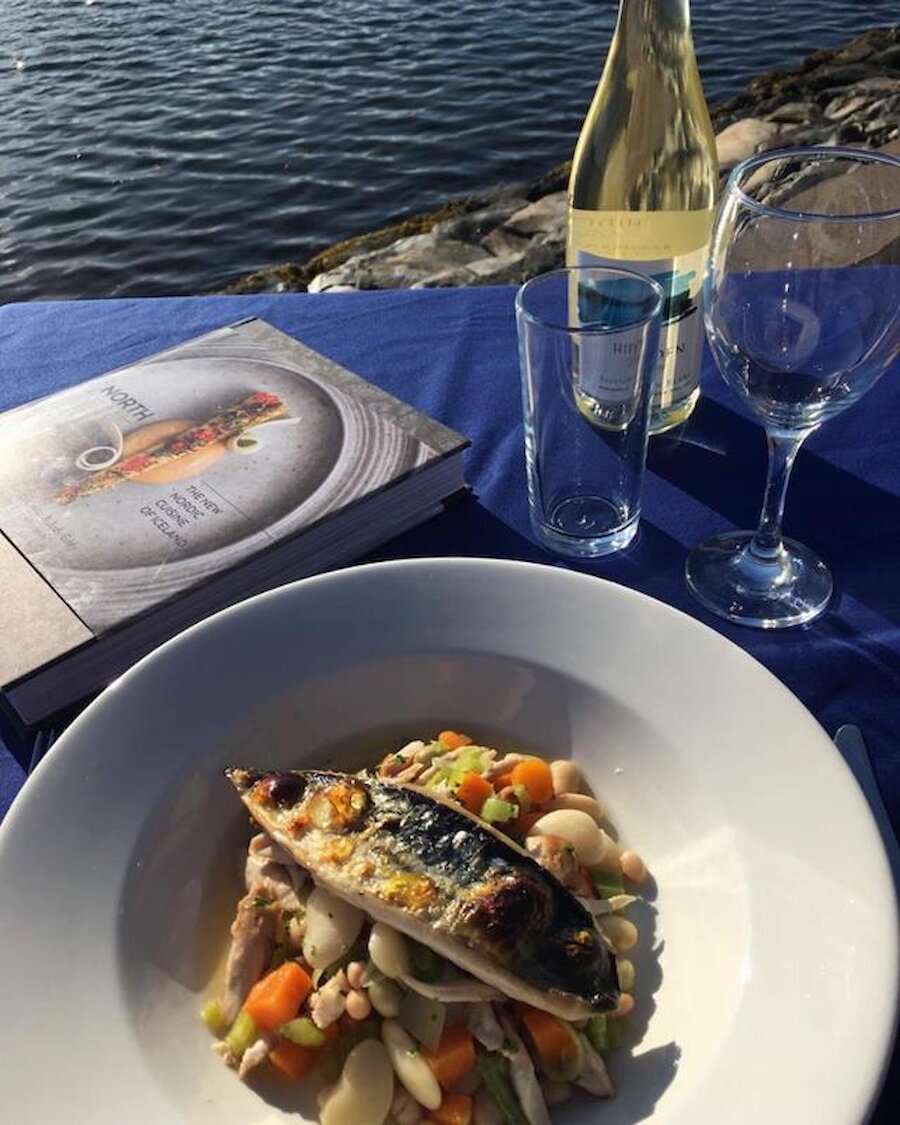

A wealth of fish

It’s no surprise that fish is still very prominent in Shetland’s larder, because the islands are surrounded by some of the most productive fishing grounds in the world. In 2021, Shetland boats landed 136,472 tonnes of fish and shellfish, worth £138.5m. In fact, the weight of finfish landed in Shetland was greater than in all the ports in England and Wales combined.

There’s cod and herring, but many more species are landed. Haddock is the staple when it comes to fish and chips, but local fish counters may feature species such as catfish, halibut, mackerel, megrim, monkfish, plaice, lemon sole, ling and the salmon that’s farmed around the coast.