Lerwick, home to around a third of Shetland’s 23,000 people, is a relatively recent arrival on the Shetland scene. How did it grow to become Shetland’s capital?

In prehistoric times, there was certainly some settlement in what is now the Lerwick area. The most prominent clue is the Iron Age broch of Clickimin, dating back more than 2,000 years, but remains from earlier periods have been found, too.

However, brochs and prehistoric communities were present all over Shetland and – although the broch site seems to have been a particularly effective one in defensive terms – there’s nothing to suggest that the Lerwick area was exceptional. The Vikings later gave the sheltered Bressay Sound – now Lerwick’s harbour – the name Leirvik, which means muddy or clay bay.

More recently, there was a hamlet – Sound – above the Sands of Sound, though it was absorbed into the town during the last decades of the 20th century.

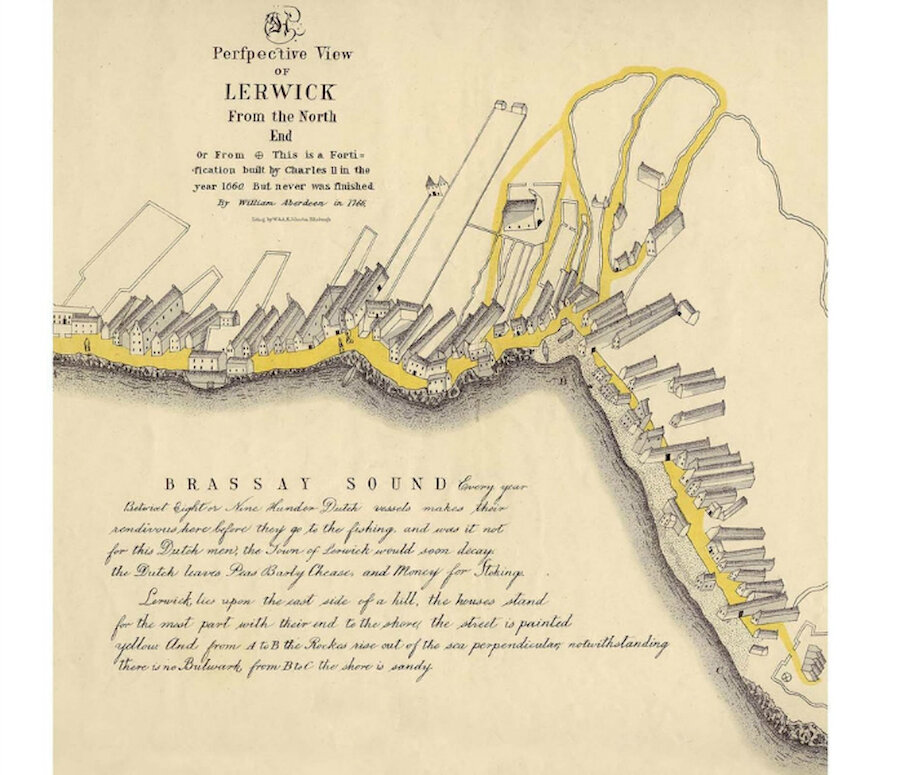

The town we know today owes its origins to international trade and, particularly, the catching, processing and export of fish. During the 16th century, Dutch fishing vessels were becoming an increasingly common sight around Shetland during the summer months. They sought out supplies locally, and trading with their crews began at a number of places, including Hollanders’ Knowe, almost three miles south-west of the original Lerwick settlement, and along Bressay Sound, where Lerwick grew up.

By the early 17th century, the rambling collection of seasonal booths along the shore was beginning to attract the attention of the authorities in what was then Shetland’s capital, Scalloway, just six miles across the hills to the west. Reports of crime and immorality prompted the demolition of the embryo Lerwick in 1614 and the same action was taken again in 1625. But the Dutch boats continued to visit, and a permanent settlement gradually became established.

Trading was aided by the construction of many merchants’ piers and warehouses, which might be combined with a home, along the waterfront. The surviving lodberries (‘loading stones’ in Old Norse) are nowadays best seen at the south end of the town centre and one of them had a starring role as the fictional home of Detective-Sergeant Perez in the BBC1 Shetland series. The Old Manse, dating from the 1680s, is on the right of the picture at the head of this article; it’s believed to be the oldest surviving building in the town.

Britain went to war with the Dutch three times during the mid-17th century and a fort above the shore in Lerwick housed a garrison of English soldiers during the first two conflicts, though not during the third, with the result that the Dutch attacked the fort in 1673 and did some other damage. But it seems that Shetland folk were happy to trade not only with the fishermen but with the Dutch military, and that close relationship persisted.

The new town became a civil parish in 1701, detached from the parish of Tingwall in which Scalloway was and is the main settlement. However, Lerwick suffered a serious setback two years later, when a French fleet attacked. It was a minor act in the War of the Spanish Succession, but a real blow to the town and in particular to the Dutch trade, the object of French hostility.

it was a minor act in the War of the Spanish Succession, but a real blow to the town

Recovery took some time and the Dutch fishing never regained quite the same importance; but other fisheries developed and Lerwick’s growth was also fuelled by the trade pursued by increasing numbers of merchants. Shetland’s centre of gravity was gradually shifting towards the town and Lerwick took over the role of island capital from Scalloway in 1708.

Prosperity may have been fragile, though: one of the major lairds, the influential Thomas Gifford, wrote in 1733:

As Lerwick chiefly subsists by the resort of foreigners to it, so when that fails it must decline, as indeed it has done for several years past, having been very little frequented by foreigners, and thereby is become very poor.

The fort was reconstructed in 1781 and named Fort Charlotte in honour of George III’s queen, though its cannon were never to be fired in anger.

By the end of the 18th century, Lerwick’s population exceeded 1,000 and Scalloway’s decline seems to have been severe. The Reverend James Sands, writing in 1797 in the Statistical Account of Scotland, noted that:

The only village in these parishes is Scalloway. It was formerly considered as the chief town of the Shetland Islands. Some families of distinction lived in it. It was the residence of the Sheriff-Depute, the seat of justice and consequently the resort of strangers from the different parts of the country. Of late it has fallen into much decay. At present there are but 31 inhabited houses in it; and the only gentleman of property, now residing in it, is Mr Scott of Scalloway, who is almost its sole proprietor.

In 1792, Arthur Anderson, co-founder of the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (subsequently, P&O) was born in the Böd of Gremista, some way north of the then town centre, which now houses the Shetland Textile Museum. He was later to enter politics and to become a substantial benefactor, establishing the Anderson High School and the Widows’ Homes.

Lerwick became a Scottish Burgh of Barony in 1818 and by 1831 the population had reached 2,750. It was by then a well-established fishing port with a growing infrastructure of docks. Hay’s Dock, where the Shetland Museum and Archives now stands, dates from 1830.

Scheduled steamer services linking Lerwick with Aberdeen and Leith were introduced in 1838.

Change of other kinds was in the air. Many of the congested Lanes, in which all classes lived cheek by jowl, were re-named in the mid-19th century to reflect the political trends of the time; for example Reform Lane. But something more radical was on the horizon; or rather, just over the low ridge to the east.

Although income from herring fishing wasn’t consistent in the last quarter of the 19th century, there was enough of it, especially when combined with Victorian optimism and civic pride, to transform the town. The better-off middle classes moved from the Lanes to a ‘new town’ just to the east.

Many handsome stone villas were constructed, laid out on a grid plan; it was a movement reflecting the trend by then established in many towns in Scotland.

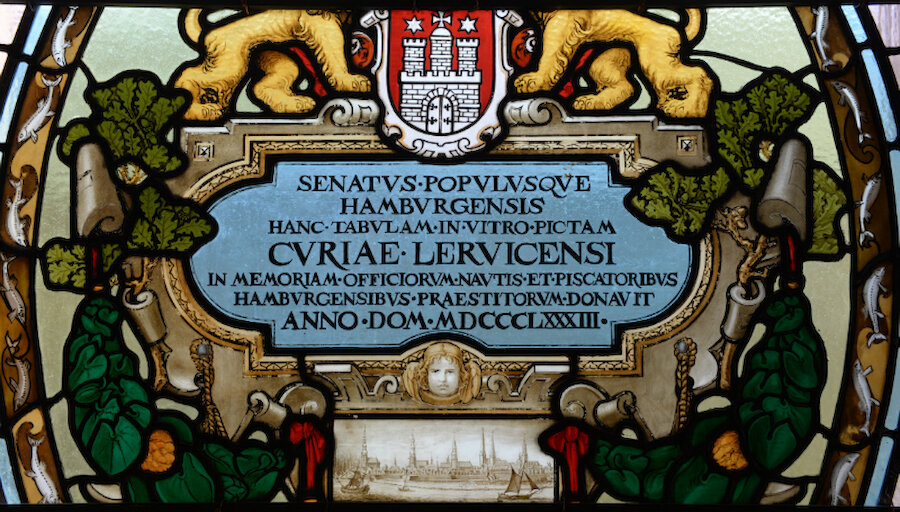

Of particular note are the exceptional stained glass windows, which justify the building’s A-Listing and are, experts say, on a par with the best secular stained glass in Britain. In the main hall, a sequence of windows narrates a substantial part of Shetland’s history, focusing on the Norse and earliest Scottish connections. Other windows, and motifs set into the roof, refer to Shetland families and to other places with Shetland connections.

One of the two contractors involved had also been responsible for stained glass in London’s House of Lords; clearly, Laurenson would accept nothing but the best.

The twentieth century saw Lerwick’s continued expansion with the building of an early Council housing development of excellent quality; in a sense, it set the standard by which later housing would be judged and several subsequent projects in Lerwick came to be recognised as outstanding by bodies such as the Saltire Society.

The town was involved in both world wars and heavily fortified by both land and sea. Both conflicts involved many Shetlanders, who were particularly valued in both the Royal Navy and the Merchant Navy for their seamanship. In those wars, the fishing industry shrank in scale, partly because of the risk to boats from enemy action but also due to loss of export markets and manpower.

However, thousands of troops were stationed in the islands, particularly during the Second World War. Catering for them, together with military construction, created jobs.

The depression of the 1930s affected Shetland and the 1950s were also difficult, notable for population decline; nevertheless, the town was home to 5,538 people by 1951. it wasn’t until the 1960s that significant growth was re-established and new investment was made, for example in the town’s first indoor swimming pool and in new fishing boats and fish processing facilities.

In the 1970s, increasing prosperity arose partly from oil exploration; service bases, shown above, were created at the north end of the harbour. There was an expansion in public services, including an excellent new library and Shetland’s first museum, together with more housing developments in the town. A roll-on, roll-off ferry terminal for the Aberdeen ferries opened in 1977.

The following decades saw many more tangible benefits flow from oil revenues. The Clickimin Leisure Centre opened in March 1985 and was subsequently expanded. It contains Shetland’s largest hall, used not only for sports but also for large-scale events including the Craft Fair, the Classic Motor Show and major concerts.

An award-winning redevelopment of the North Ness area saw the opening of the new and engrossing Shetland Museum and Archives in 2007, followed in 2012 by Mareel, a superb arts centre with twin cinemas and concert hall.

The Lerwick Port Authority continued an impressive programme of investment, with a brand-new ferry terminal in 2002, extensive new wharfage, and facilities to handle an increasing amount of leisure traffic in the shape of cruise liners and yachts.

Yet, despite the growth of the leisure market, fishing and fish processing remain mainstays of the port and the town, with a new fish market just completed.

Although a population of just over 7,000 makes Lerwick a relatively small town by most standards, the facilities it offers compare well with those of larger places. Partly, that’s because Lerwick actually serves 23,000 people; also, unlike any other British town of its size, the nearest cities are nearly 200 miles and a ferry or flight away.

There’s an acute general hospital, the Gilbert Bain, featured in the BBC1 series, Island Medics; a Sheriff Court; offices of government departments or agencies, such as Jobcentre Plus, Scottish Natural Heritage and the Care Commission. All the major banks are represented and there’s a wide range of professional services, from solicitors and accountants to architects and web designers.

BBC Shetland produces a wide range of local programmes and contributes radio and television content to the national networks. We also have a locally-owned independent radio station, SIBC. The University of the Highlands and Islands has one of its two Shetland campuses in Lerwick.

As a busy port, Lerwick has a customs and immigration presence, a coastguard station and one of Shetland’s two lifeboat stations. There’s extensive marine engineering support

However, there’s another reason why the facilities are so extensive, and that of course is because of the investments made over the past 35 years in sports, arts, culture and heritage; in these, too, the extent and quality of provision equal or exceed those in much larger places.

the extent and quality of provision equal or exceed those in much larger places

So, it may be a ‘peerie’ (small) town, but it’s well-rounded, an open community that’s been welcoming folk from all over Europe and the world for centuries. A notably confident place, too, it’s able to pull off events such as the largest fire festival in Europe or host the Tall Ships Races and the international Island Games.

All in all, Lerwick feels like a decidedly self-contained and surprisingly cosmopolitan island capital.