This is the last place. There is nowhere else to go.

For we have walked the jewelled beaches

at the feet of the final cliffs

of all Man's wanderings.

This is the last place

There is nowhere else to go.

From The Song Mt. Tamalpais Sings by Lew Welch

I am not lost. I know where I am. I am in Shetland.

Not ‘on’ Shetland. This was drummed into me by Rayleen, a former editor of The Shetland Post. Well, bellowed into me, at that time a fumbling know-all soothmoother reporter. A lot of those passed through the paper’s portals.

“You may be ON a boat,” she said, very loudly, on the single, entirely memorable occasion I submitted copy stating that someone was currently on Shetland. Or that the situation on Shetland had deteriorated. Or something. “Or you may be ON holiday. Or for all I know and care ON DRUGS. But as far as I can tell you are neither vacationing nor floating. Nor are you in some kind of pharmacological fugue. But you are currently IN SHETLAND, and don’t you forget it.”

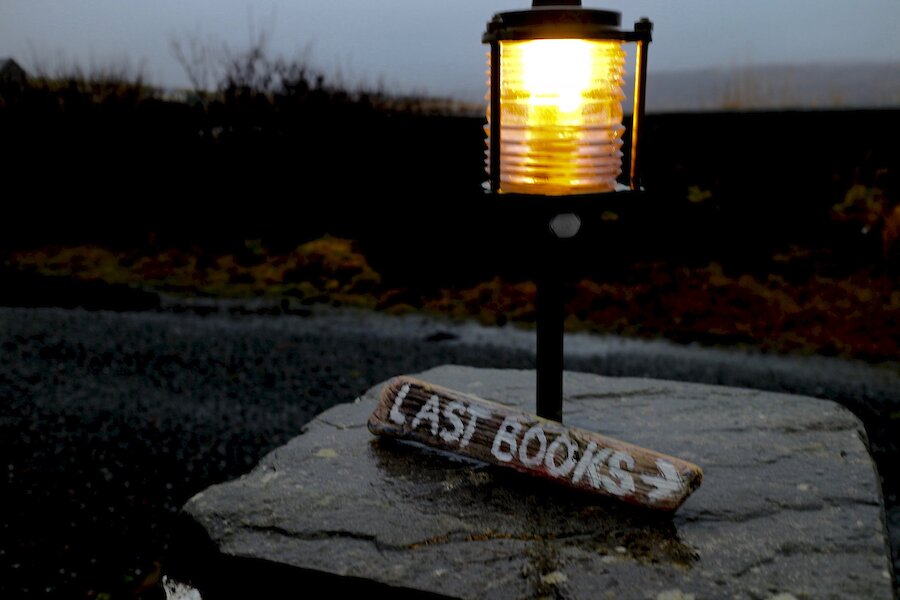

And I never have forgotten. Tonight I am in the part of the Shetland Mainland called Ramnavine. In Quidawick, to be precise.

In Shetland. Need I mention that it is never ‘The Shetlands’? This is a singular place.

The walk, this November night, is from sea to sea, Aest Ayre to West, beach to beach, North Sea to Atlantic. The storm is gathering its forces in the sky, which is moon-blue behind heaving, shifting cloud. The wind is moving round from north west to south east, leaving the big, Atlantic waves crashing onto the West Ayre, over the stile and across 200 metres of field. I am not going there, not after dark. Rocks come hurtling through the shifting air on a night like this. It’s dangerous.

And this is nothing. Mild, compared to the hurricane that deposited a boulder on the roof of the Karaness lightkeeper’s house, on a clifftop 200 feet above the sea. A stone so big it took three men to move it. And that is a mere piece of nature’s tricksy bluster, compared to the tsunami, the ‘200-year-wave’ they say explains the line of sofa-sized rocks in a ragged line along those same cliffs.

Or it could be a 100-year-wave. In which case it’s overdue and might arrive tonight. Oh well. I’m ready. Pretty much,