An ex-whaler sits before me; youthful eyes glinting from a face etched by years of wind and waves.

"When I was a lad, there was none of this big ships in the Lerwick harbour; there were herring drifters. From north of the Bressay ferry terminal all the way to Rova head there was nothing but herring stations where hundreds and hundreds of tonnes of fish were gutted and processed."

"The herring came down from Iceland and down the coast of Shetland to the mainland of Scotland", he continues. "The boats didn't have all this fancy equipment to find them either. You watched for the solan geese [gannets] diving. Where they dove that's where the herring was."

"My father and brother were coopers, making barrels for different stations, and when all the boats was in with the bad weather you could almost walk across the water to Bressay!"

"My mother was a gutter cleaning the herring ready to be salted for East Germany, Poland and many other areas. Salt herring was the in thing," he says, catching his breath as his cold coffee lays abandoned on the table. "We used to have it for dinner once or twice a week, if we were lucky."

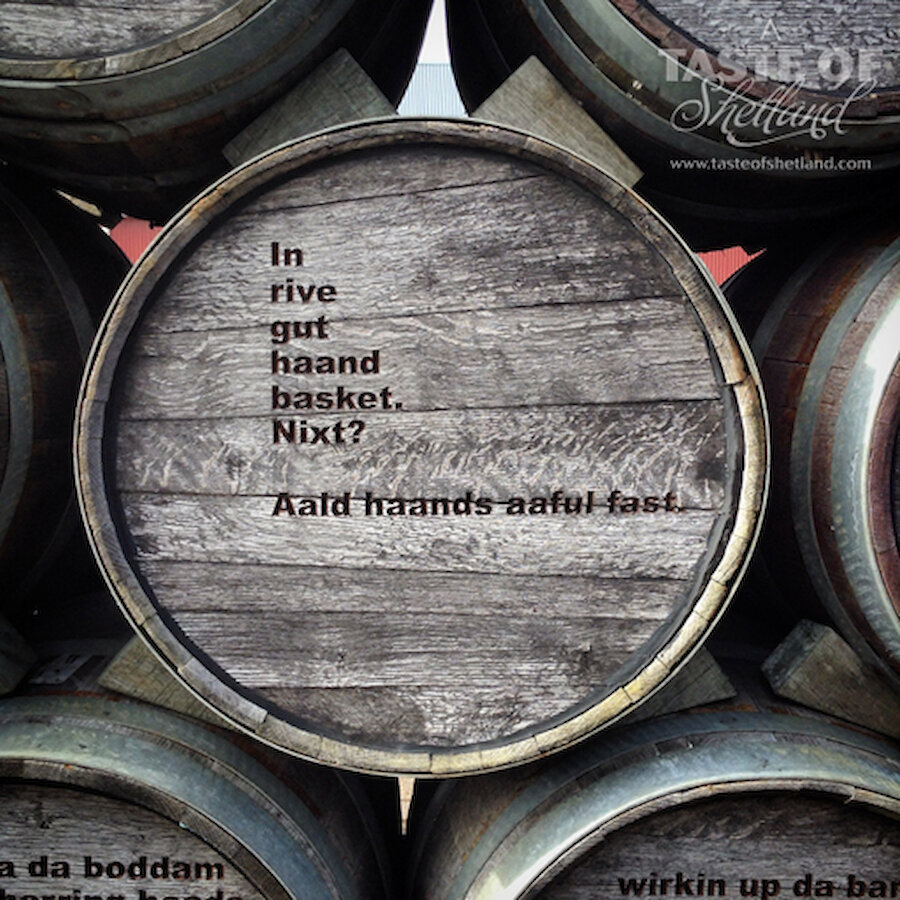

The herring fishery changed women's lives here in Shetland. For the first time they had the chance to earn their own money while the men were away at sea; to have independence and a life outside of crofting, knitting and domestic service. In 1909 the Shetland herring industry employed 14,000 people, 1670 of them women. This figure doesn't include the hundreds of women who travelled south to gut at stations throughout Scotland and England.

Shetland has a rich maritime heritage, and, in the 18th and 19th centuries, it dominated the herring fisheries in Europe.

Times have moved on, the herring stations have closed and Lerwick, Shetland's main town, is now home to Europe's largest primary pelagic fish processing plant: The Shetland Catch. It's location, in the heart of the mackerel and herring fishing grounds, contributes to its success, as does the shareholders reinvesting profits back into the company. Shetland, Scottish, Irish, Norwegian, Swedish and Danish vessels all land their catch here while the fish are at peak freshness.

The Shetland Catch was set up in 1986 as a joint venture between the Lerwick Harbour Trust, The Shetland Fish Producers Organisation and Jaytee Seafoods. Now it is half owned by Norway Pelagic, but it still operates as an independent company.

Shetland Catch Open Day

This year saw the 25th anniversary of the Shetland Catch. To celebrate this milestone, on June 14th they held an open day, where more than 1000 visitors explored the processing facility. One of four giant cold stores, which normally hold 11,500 tonnes of fish, was converted into a venue where a photo gallery displayed the history of the Catch and tables and chairs decked out with white tablecloths were set up for a buffet.

Visitors were treated to the end-product of the Catch with a delicious Shetland seafood buffet including Shetland Mussels with salsa vinaigrette, smoked mackerel and tatties, scallop ceviche, herring pate on oatcakes and roast Shetland lamb and rhubarb chutney on bannocks. Home bakes and refreshments were also on offer (we do love our cakes!).

Children were catered to with balloons and keepsakes to take away as well as a children's section for colouring in and learning all about sustainable fishing.

On the Friday before the open day a celebration dinner dance was held in the Shetland Hotel for Shetland Catch staff, where gifts were presented to mark long service to the company. Following the open day the celebrations were rounded off by a dinner held for the company's friends, customers and suppliers from around the UK and Norway.

According to the wider seafood industry's So Much To Sea, whose very popular exhibition pods and seafood film were on display, the seafood industry in Shetland is worth £300 million per year, surpassing the value of the oil, gas, agriculture, tourism, and creative industries combined.

Managing director of the Shetland Catch, Simon Leiper, said:

"It is often difficult for people to fully appreciate the sheer scale of our operation, so we decided to invite the Shetland public in to see the process for themselves.

It was good to see so many people come along to the open day and see how it has grown over the years."

Two pelagic fishing vessels, the Adenia and Charisma, were open to the public as was the restored herring drifter the Swan, originally built in Lerwick in 1900. A spokesman aboard the Swan explained that there used to be 400 herring drifters like her fishing the local waters, now there are 9 pelagic vessels.

What struck me about the factory during the Open Day was how quiet and clean it was. All the machinery was shut down so I planned a return visit to see everything in action. I returned to the factory a month later, one week after the first catch of the year was landed by the Scottish vessel the Sunbeam. After donning wellie boots, a hair net and protective coat I was given a very thorough tour by Paul Ratter, the quality control manager.

When the Shetland Catch opened, they were only processing 150 tonnes of fish per day. Now, with reinvestment and improvements in technology, they can process up to 1000. Their new Baader filleting machine can fillet five fish per second, Paul explained. 360 tonnes of fish were being processed while I visited. In stark contrast to the open day it was loud, wet and fast. Factory employees were all wearing ear plugs and waterproofs.

Operation was paused for a few moments as I watched Paul shut down the machines and remove a whole herring jamming the works. The gentleman in the selecting area then got a few minutes' break from sorting 360 tonnes of fish fillets.

Scottish Pelagic Sustainability Group and MSC certification

In 2005-6 The Shetland Catch became interested in MSC certification, but to do so they had to get everyone in the North Sea herring and Western mackerel fishery involved. The Shetland Catch were instrumental in setting up the Scottish Pelagic Sustainability Group (SPSG), established in 2007 specifically to get these herring and mackerel fisheries MSC certified.

John Goodlad, Chairman of the Shetland Catch explains that it is a very rigorous procedure to become MSC certified.

"It's similar to being audited. There are three core principles: 1. state of stock management and quota, 2. management of fishery, and 3. what impact the fishery is having on the wider environment."

Fishing practises must not lead to overfishing or depletion of target stocks, effective management must promote responsible and sustainable fishing and any damage to marine ecosystems must be minimised.

The history of pelagic fishing in the early 2000's wasn't very good, plagued by over quota landings. By 2008 the North Sea herring fishery had become MSC certified, and by 2012 all Scottish pelagic fisheries (three herring and one mackerel) were certified. (Note: The MSC certification on mackerel has been temporarily suspended pending resolution of the mackerel dispute with Iceland.)

Goodlad explains:

"Becoming MSC certified is something we are very, very proud of. It's not just the Shetland Catch by itself, it's the whole Scottish herring fishery."

"When MSC certification was rolled out 20 years ago the theory was that the consumer would be willing to pay a little bit more to buy MSC certified fish. In reality, this hasn't been seen in practice, but it has been a huge success."

"Being MSC certified gives you access to discerning markets that only accept MSC certified fish. Russia, the Ukraine and Nigeria are big markets, as are Germany, the UK and France."

"It demonstrates to the public, press and politicians that the Scottish pelagic industry is fishing in an environmentally conscientious way. We are doing the right thing."

Only 8% of the global fisheries (in tonnage) is MSC certified, and 40% of the UK fisheries are. This speaks volumes.

In terms of the future, Leiper continues:

"We will continue to build on our key strengths - our strong geographical position close to the fishing ground, our state-of-the-art processing facility, and our solid customer base, while focusing on our environmental responsibility and long-term sustainability."

The SPSG held its most recent meeting on board the restored Swan. Goodlad explains, "It is very fitting we should meet on board the Swan. It shows that the modern pelagic industry has a very proud and rich history which we should never forget."

"They got turned into fish and bone meal and if the wind was in the east Lerwick was rather smelly!"

I guess things don't always change that much after all.

Salt Herring Salad

Course: Main

Servings: 4 people

Prep Time: 15 minutes

Ingredients:

- Medium-sized onions - 5

- Herrings - 3

- Peppercorns - 12

- Salt and pepper -

- Vinegar - (to cover)

Instructions:

- Wash, skin and clean herring thoroughly.

- Remove bones from head downwards, split open from back and cut into 8 or 10 pieces.

- Lay in pie dish with alternate layers of onion, add seasonings, cover with vinegar and allow to stand overnight.

- The salad is ready for use the next day. The vinegar softens the bones and the salad will have all the appearance and taste of cooked herring.

- The addition of boiled sliced beetroot or slices of cucumber is an improvement.

Margaret B. Stout's book Cookery for Northern Wives can be purchased from the Shetland Museum & Archives gift shop.

Article adapted, with permission, from one written by Elizabeth Atia for Fish on Friday, due to be published later this year.