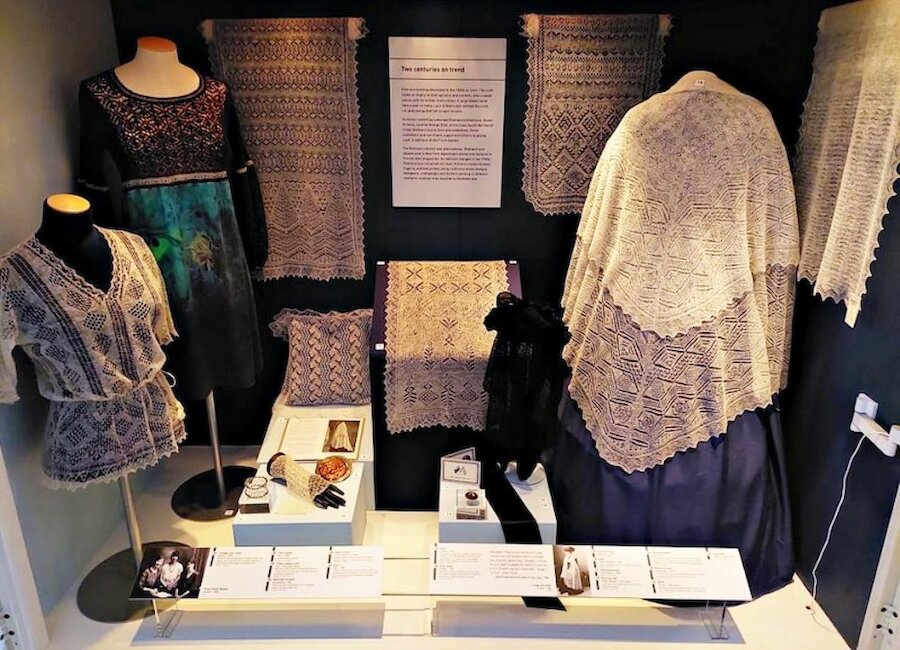

The display builds on the museum’s original lace exhibition and is one of the outcomes of a two-year Lace Assessment Project, led by textiles curator Dr Carol Christiansen and funded by Museums Galleries Scotland.

Today, Shetland is recognised worldwide for its knitting tradition, particularly Fair Isle patterns. However, the fine knitted lace produced in the islands is perhaps less well known than it once was, and a new display at the Shetland Museum and Archives aims to put that right. It demonstrates the astonishing skill of our fine lace knitters and, spanning two centuries, it’s simply awe-inspiring.

Drawing on the museum’s rich collection of over 400 Shetland lace pieces, the items on show date from the mid-nineteenth century to the present day.

Dr Christiansen explains: “The craft developed within the Victorian period and was firmly established within the fashions of that time. It has continued to look to contemporary fashion throughout the 20th century by applying long-standing patterns to new styles. Throughout the craft, other fibres were used, especially for special orders, such as silk, mohair and cotton.”

She adds that she and her colleagues have been studying the topic for many years.

“Since 2009, we have done extensive research on Shetland knitted lace design and the lace industry, which began in the late 1830s. We wanted to revise our permanent display to reflect our expanded view of its history and importance and to include new, important donations received in the last decade.

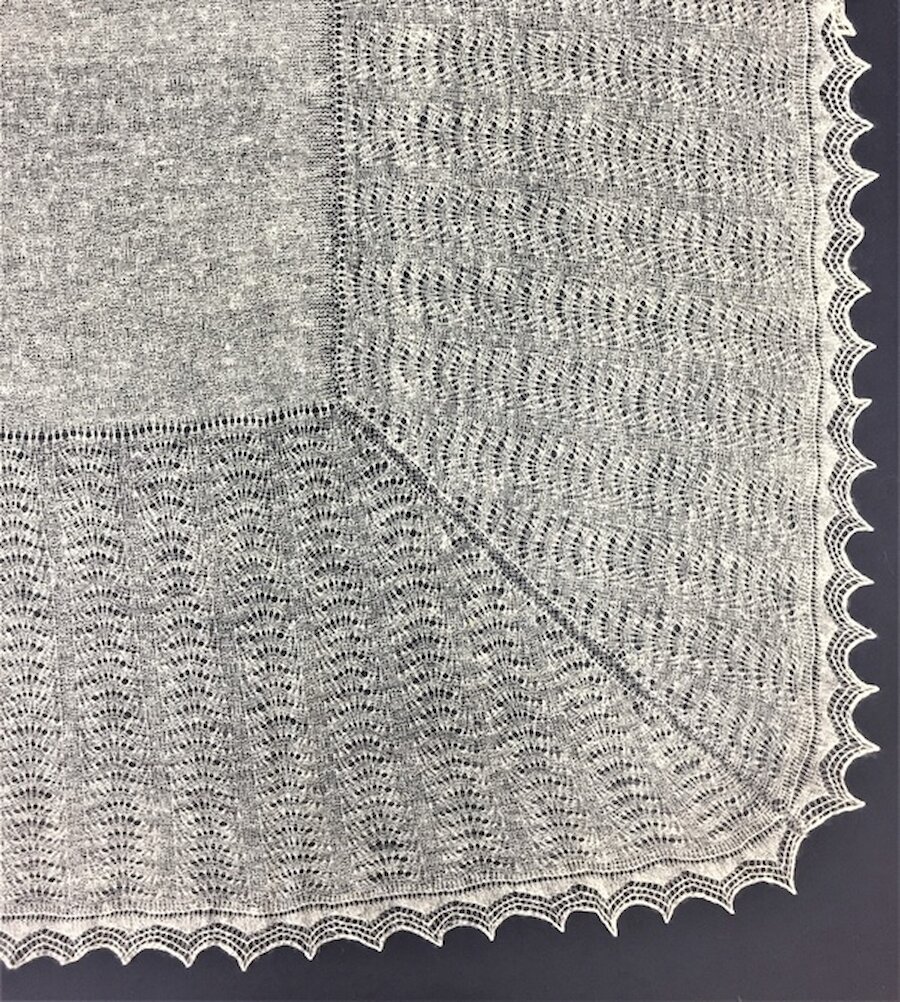

For example, one item is the test piece for the stole that was gifted to Queen Victoria on her 80th birthday in 1899. Two pieces were made - the best went to the Palace, and the other is here on display." Part of the stole is shown below.

“A second important outcome of the Lace Project is our new understanding of why Shetland lace was designed in the way it was. We wanted to document and show how, in particular, the borders of lace shawls were a really crucial element in the design of the shawl – much more so than the centre, which often people focus on. As shawls were developed as a fashion item in the 1840s onwards, when women’s skirts were expanded outward with a crinoline, it is typically the border that is shown off as it is draped onto the skirt, and this is in fact the more complex part of the design. In this case, design definitely followed fashion.”

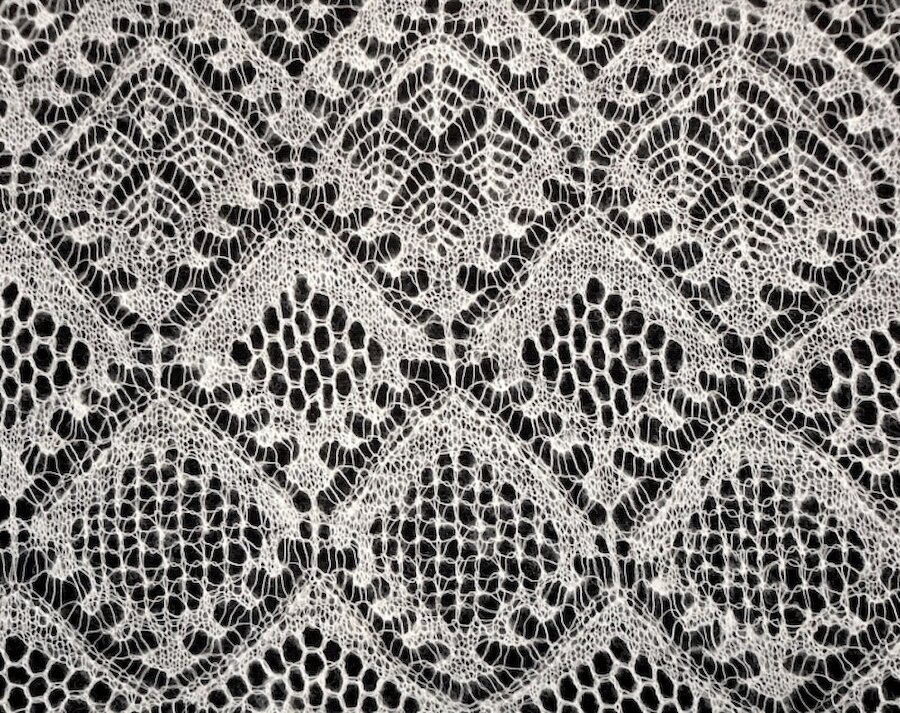

A complex border, featuring diamonds set within knotty waves, each with different centres, is shown below.

Another highlight of the display is an exquisite lace blouse from the 1920s or 1930s, shown below. It is one of a number of fashionable and daring lace blouses recently donated to the museum collection, all of which are extremely well made and designed with extraordinarily fine spinning. The blouses signify the modernisation of the craft of Shetland fine knitted lace, proving that it could respond to contemporary women’s fashion after the corseted Edwardian period. One of the remarkable things about such blouses is their weight, or rather their lack of it. The blouse with jabot weighs just 18.2 grams, or 0.64 ounces.

Dr Christiansen emphasises that achieving this was dependent as much on the skill of the spinner as that of the knitter. “It was necessary to maintain an extremely fine yarn at an even diameter for a very long length. It is documented that an 1892 shawl weighing 2.5 ounces was made with 10,200 yards of two-ply wool. In this case, the hand-spinner had to spin that length of single yarn twice, and then ply it. If the hand-spinning wasn’t consistently made with the same amount of fibres, this was visible in the knitting but sometimes not until the knitter had worked some length beyond. Highly skilled knitters relied on hand-spinners they could trust to make consistently fine, but strong yarn.”

Very rarely, anomalies do appear.

The project is fascinating not only for the light it has thrown on design, but also for its glimpses of social norms and trends.

One of several blogs on the Shetland Museum and Archives website explores the history of face veils, which might be worn in many contexts. They “signalled social status, expressed femininity, reservedness, even coquettishness”.

However, veils also provided practical protection from sun, rain and airborne dirt and dust. Veils were made for infants – like the one above – as well as for adults.

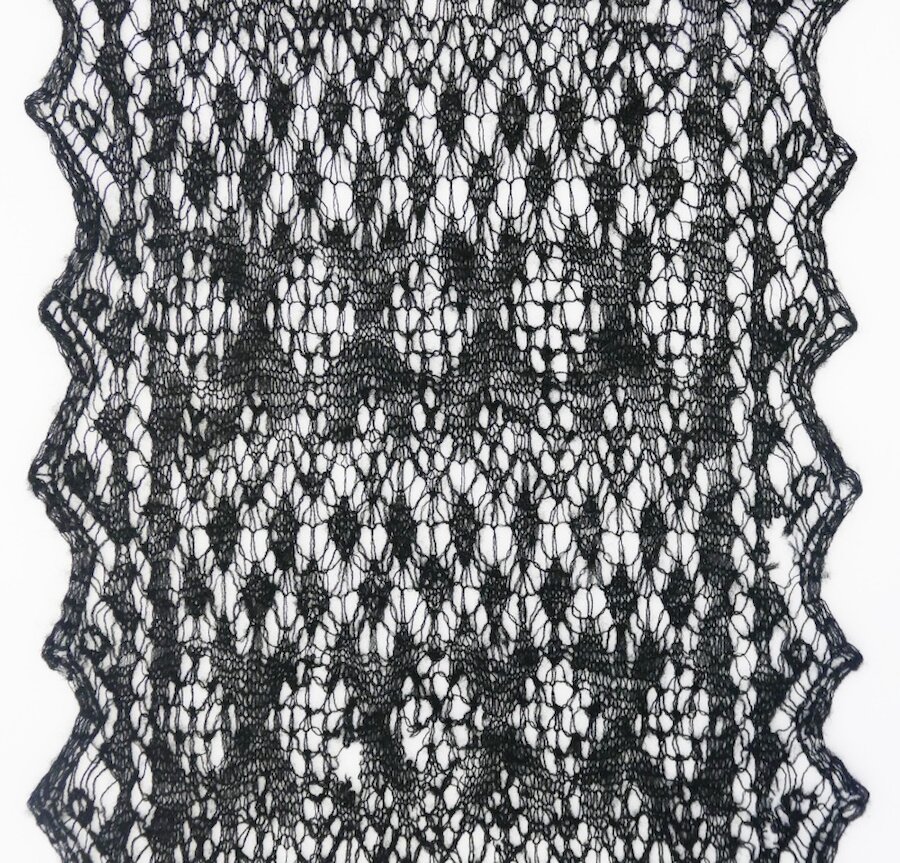

Lace was worn in many contexts; veils were necessary during periods of mourning and Dr Christiansen explains that for mourning (12 months) and half-mourning (6 months), shawls and stoles were required in black and grey respectively. “Black was always dyed because Shetland black wool is really dark brown; grey wool was easy to obtain from Shetland breed.” The centre of a mourning scarf is shown above.

Although the exhibition illuminates centuries of lace knitting, it also demonstrates that the tradition is alive today, with two contemporary pieces also forming part of the display. These show how traditional lace patterns have been reinterpreted and are still relevant – and in demand – today.

The first is a bold lace and silk dress by Angela Irvine of Whalsay, seen on the left of the photograph below, which uses a Shetland black lace yarn for the bodice; the skirt is printed silk. The second is a delicate silver and bead lace cuff by Helen Robertson of Northmavine.

The project involved photographing and assessing those 400 or so items. Many were studied in great detail, beginning with those which incorporate unusual or unique motifs. Variations from ‘standard’ patterns were recorded in order to build a better understanding of how the craft evolved over time, and how different knitters contributed to that evolution.

The Shetland Museum’s textile collection has been recognised as a Nationally Significant Collection since 2013. The Lace Assessment Project and the new exhibition were funded by Museums Galleries Scotland’s Development Fund for Recognised Collections. The series of blogs following the progress and findings of the project can be found on the Shetland Museum website.

What is the future for Shetland lace? The museum is doing what it can to support the craft; Dr Christiansen has established a Contemporary Crafts Collection, which includes items bought directly from highly-skilled makers working today, rather than simply waiting for donations of work. Some established makers aren’t yet represented in the collection and that will be rectified. Such purchases have been generously assisted by the National Fund for Acquisitions, but other sources of support may also be available. As part of this effort, conversations with makers about their life in the craft will be recorded.

Other ideas which might be explored include appointing a lace knitter in residence, who could teach, perhaps create contemporary patterns and exhibit their work.

It’s to be hoped that the tradition will survive, continuing to demonstrate the extraordinary skill, patience and artistic flair that are so much in evidence in the museum display. Shetland lace is an outstanding craft and deserves to be valued and nurtured.

I am very grateful to Dr Christiansen for her assistance in preparing this article.